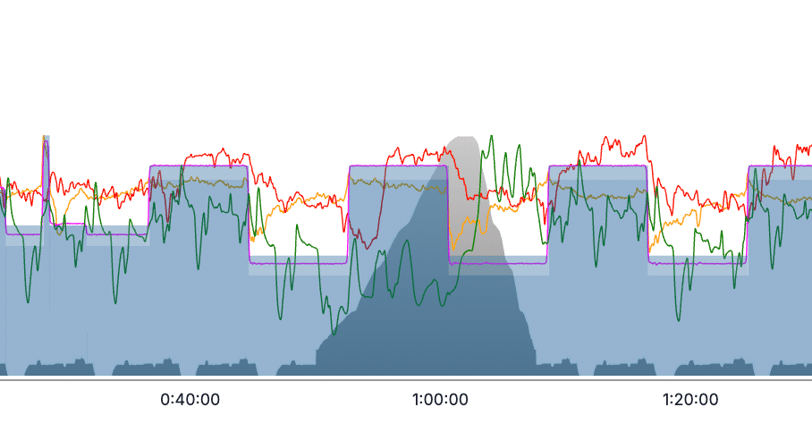

Modern cycling lacks panache. Athletes at all levels are caught up in the numbers game to guide their training: what’s my functional threshold power (FTP), heart rate, VO₂ max? The devices that measure these metrics are tools that provide valuable insights—but becoming overly dependent on data can overshadow an athlete’s ability to gauge effort through perceived exertion (Dunbar et al., 1992; Eston & Williams, 1988).

The Norwegian Method is the newest buzzword in the endurance community. It’s a type of training that heavily relies on systematic lactate testing and precise intensity control. While you can’t argue with the results and performances of Norwegians like Kristian Blummenfelt, Gustav Iden, and Jakob Ingebrigtsen, their training requires a massive amount of resources, laboratory access, and constant testing—making it impractical for most people. More importantly, it underpins the idea that endurance performance is just about hitting the right numbers like a machine, when in reality, training is far more nuanced.

VO₂ max is probably the single most misunderstood metric in endurance sports. It's often treated as the ultimate indicator of athletic ability—but that’s an oversimplification. While VO₂ max measures the maximum rate of oxygen utilization (Bassett & Howley, 2000), it doesn’t directly predict endurance performance. True endurance depends on muscular efficiency, metabolic flexibility, lactate threshold, mental resilience, and other adaptations that VO₂ max alone can’t capture.

Everyone is preaching the benefits of VO₂ max training and it’s often touted as the golden physiological marker. VO₂ max is often associated with quick improvements, often promised through high-intensity interval training (HIIT). But that’s misleading. Many studies showing VO₂ max improvements are short-term, using untrained or moderately trained subjects—rarely world-class athletes (Bassett & Howley, 2000). Endurance isn’t built in weeks; it’s forged over years through consistent training that improves stroke volume, movement economy, and psychological toughness.

Sport is more than science—and that’s part of the appeal! I think there’s a joy that I forgot, and I think most people forget as they grow older or begin to become more serious about athletic pursuits. People begin to replace the fun and child-like exploration with a mindset that mirrors work. Yes, training is hard work and at times will hurt, but there should be a sense of fun at its core. There’s something deeply human about endurance sport—the times of suffering in solitude, the small mental battles and victories, the belief that your body has more in the tank, even when the numbers say otherwise.

The numbers that are plastered all over Strava, Garmin, and plague group ride conversations like VO₂ max, FTP, and lactate threshold are useful—they help us navigate training, identify trends, and prevent burnout. But it’s important to remember they are not the sport. We are not professional statisticians. The numbers don’t feel pain. They don’t feel joy. Numbers will never bonk on a long ride. But they will also never know the feeling of discovering another gear that you didn’t know you had.

Pushing your limits never goes according to plan or rarely is it quantifiable. A personal best (PBs) is usually ugly, messy, and happens unexpectedly. It’s when you ignore your bike computer and chase the wheel in front of you. It’s when you go all-in on that local climb because your legs feel good and the bike feels like it’s dancing under you; not because Training Peaks said today was a “Suprathreshold ride with XYZ efforts.” While unexpected, these PBs aren’t accidents—they’re earned. And funnily enough, they're often the very moments where growth happens—growth beyond the physiology.

Use the data. Respect the science. But don’t forget: you are not a lab report. You are an athlete. And the most powerful metric is still your own belief.